NEW ENCYCLICAL IS A CRI DE COEUR FROM POPE FRANCIS

I can already imagine the criticisms of Fratelli Tutti, the new encyclical by Pope Francis on fraternity and social friendship released yesterday, October 4. They’ll accuse him of interfering in politics and the economic sphere, being naïve about human nature, overreaching his authority as a religious figure.

In a sense, they would be right. Defining religious authority narrowly, the Pope would be guilty on all counts.

And yet, and yet…

It can be all of these things, yet be absolutely necessary at this moment in the history of our planet. Francis has issued a cri de coeur to all people of good will. It is a call to our better selves, an astute reading of the Signs of the Times, a reminder that simple virtues like love, compassion, kindness and openness to the stranger are essential ingredients to the healing of our common woes.

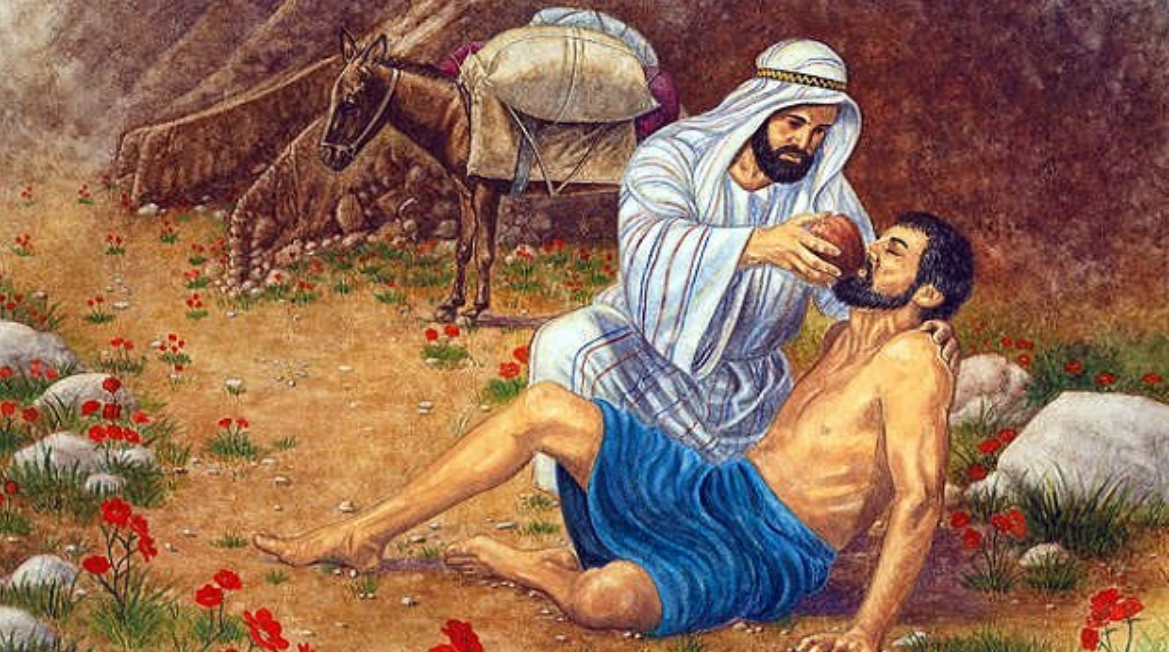

One thing Fratelli Tutti is not: a religious tract. Its theology is simple and universal, certainly not unique to Catholicism. The Good Samaritan. Matthew 25. The Golden Rule. These staples of basic Christian moral teaching form the foundation for his appeal. Francis also finds common cause with other faith traditions with references to Ghandi, Rabbi Hillel and Grand Imam Ahmad Al-Tayyeb to underline the universal reach of his message.

Francis is ideally suited to issue this call to conscience. A religious leader yes, but more than that, he remains one of the world’s leading moral figures in a world sorely in need of them. He is acutely aware of his own failings and those of the Catholic Church, but willing to accept the mantle of what Henri Nouwen called the “wounded healer.” This humility permeates the text, giving it a much-needed authenticity and compassion for the brokenness of others.

What I offer here are first impressions. By all means, read the encyclical yourself. Its prose is simple yet profound, accessible to believers of all traditions as well as non-believers. It is also rich. For every observation that touched me, there are probably ten others I don’t have room to mention.

Like many encyclicals, Fratelli Tutti begins with a critique of current events. Global conflict, natural disasters flowing from climate change, the growing fear and loathing of immigrants, and the rise of right-wing populism. Francis sees the covid-19 pandemic as a crucible that has accelerated these existing trends, bringing out both the worst and, in some cases, the best in our nature.

“The pain, uncertainty and fear, and the realization of our own limitations, brought on by the pandemic have only made it all the more urgent that we rethink our styles of life, our relationships, the organization of our societies and, above all, the meaning of our existence,” he writes.

The current economy, with its foundation in liberal individualism, comes in for scathing criticism as the source of many of the above crises. With radical self-interest at its core, global liberal economics strives to homogenize differences between peoples and countries, while concentrating economic power into fewer and fewer hands.

Followers of papal encyclicals will be familiar with this critique. It was a strong theme in the writings of St. Pope John-Paul II and has been a common characteristic of Francis’s many statements. In Fratelli Tutti, he reassembles many of his past concerns into a tightly woven diagnosis of our current struggles.

But it would be a mistake to dismiss this encyclical as familiar territory. Francis makes some crucial distinctions that require attention. The term “populism” has been hijacked, he says, to refer mainly to rising grassroots movements against immigrants, those with other skin colours, or the ill-defined “elites.” But true populism has, throughout history, often been the source of improvements in society such as human rights gains or the battle against poverty. Today, however, Francis notes that too often popular fear and anxiety are exploited by demagogues for their own purposes. He does not name names, but it is not difficult to come up with a short list.

And Francis does not ignore the potential for evil to be done in the name of religion. He reminds us that in the story of the Good Samaritan, the first two people to pass by the wounded victim of robbery and assault were religious leaders. “It shows that belief in God and the worship of God are not enough to ensure that we are actually living in a way pleasing to God.”

Francis’ foray into politics is a broad-brush approach. He isn’t talking about partisan fighting or the cut and thrust of electoral campaigns. But he is not afraid to use the word, nor apply Catholic social teaching to how societies work together for the common good. In place of competitive politics, with its winners and losers, he offers a “politics of love.”

At first, this sounds incredibly naïve. But he argues there really is no other choice if we, as brothers and sisters together on this planet, are not to descend into despair and self-destruction. He refers in passing to the many ways people have been oppressed and victimized, arguing that there needs to be true justice, yet also through a process that leads to reconciliation and forgiveness.

“This does not mean impunity,” for the perpetrators, he adds. Or simply “forgiving and forgetting.”

“Those who truly forgive do not forget. Instead, they choose not to yield to the same destructive forces that cause them so much suffering. They break the vicious circle; they halt the advance of the forces of destruction.”

In everything, Francis founds his reflection on God’s infinite love for humanity. In doing so, he makes a profound case for the good that organized religion has done and can continue to do in society. “We are convinced that ‘when, in the name of an ideology, there is an attempt to remove God from a society, that society ends up adoring idols, and very soon men and women lose their way, their dignity is trampled and their rights violated,” he says, quoting his own words to religious leaders gathered in Albania in 2014.

In a nod to the desert mystic Blessed Charles de Foucauld, Francis reminds that that true surrender to God comes in identifying fully with the poor and abandoned — “…only by identifying with the least did he come at last to be the brother of all. May God inspire that dream in each one of us.”

–Joseph Sinasac, Publishing Director, Novalis Publishing