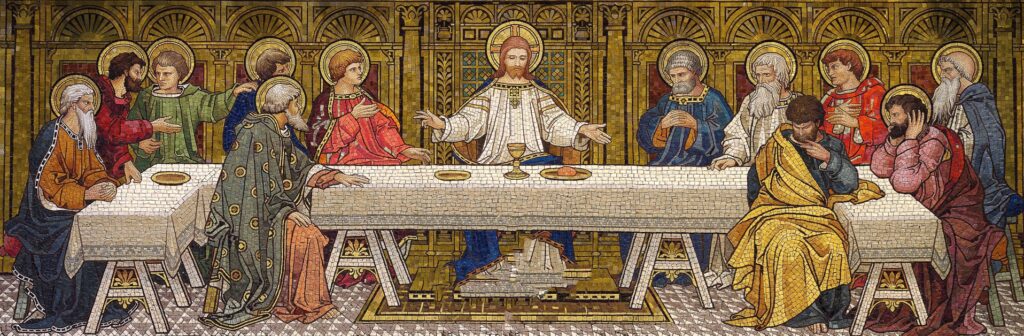

CELEBRATING THE FEAST OF THE BODY AND BLOOD OF CHRIST

I was fortunate enough to work for several years at a parish that was richly diverse in culture. The church was located near a major airport and demographically expressed the patterns of immigration. For many years, it has been predominantly Italian, then many folks from the West Indies and Caribbean settled in the area, accompanied at the same time by a large population of people from Goa. There was a significant group of Irish and some French from much earlier waves of immigration. Each year on the feast of Corpus Christi we would host a large parish celebration. We celebrated Mass in a way that incorporated the cultural richness of the community. The entrance procession included a multi-coloured liturgical dance. Prayers of the faithful were prayed in a variety of languages. The recessional morphed into a procession around the block. And then there was feasting. Jerk Chicken. Lasagna. Irish Stew. Lamb Curry. Macaroni Pie. Cannelloni. Baclava. The banquet was lavish. There were games and music. Everyone left with full stomachs and full spirits.

This annual experience embodies a marvellously robust and inclusive understanding of eucharistic theology, devotion and piety. It is an encounter of the eucharistic presence of Christ in the Mass, in the companionship of community, in shared meals and in popular devotional practices.

The development of eucharistic devotions, historically, did not always come from a place of such balance. Sometimes they developed as a surrogate for the reception of Holy Communion when theologies of human sinfulness overshadowed theologies of God’s gracious love and mercy. People had stopped receiving Communion thinking they were unworthy, but their longing for connection with Christ was profound and so the practice of gazing at the consecrated host developed. Sometimes a fear of losing a sense of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist led to a neglect of teaching about the real presence of Christ in the people, the priest and the Word of God. A theologically sound and humanly healthy understanding of the Eucharist for Catholics is one in which we embrace the real presence of Jesus among us in the Eucharistic bread and wine, but also in the transformed community of believers. These ones, who have received Christ into their bodies are walking tabernacles, where we can also meet the risen Lord. Our quiet prayer before the Blessed Sacrament in a church and our public demonstrations of eucharistic faith on the street ought to lead us to love more deeply both God and our neighbour. (Mons is the Latin word for showing… and is the core of the word monstrance in which the consecrated host is held for prayerful gazing.)

The struggle for balance is a perennial human struggle. Aristotle articulated it as seeking the “golden mean.” We are, it seems, most often either approaching this balanced centre or overshooting it. Once in a while, however, we joyfully dwell in precisely this place of wholeness. Our celebrations at Our Lady of the Airways (yes, that was the name of the parish near the airport), seem to be such a place for me.

Christine Way Skinner is a doctoral student at Regis St. Michael’s at the Toronto School of Theology and has been a lay pastoral minister for more than 30 years. Together with her husband, Michael, she has parented 6 wonderful children. She has written a number of books for Novalis on living the Catholic faith for both adults and children.