PAUL’S (ECOLOGICAL) CONVERSION

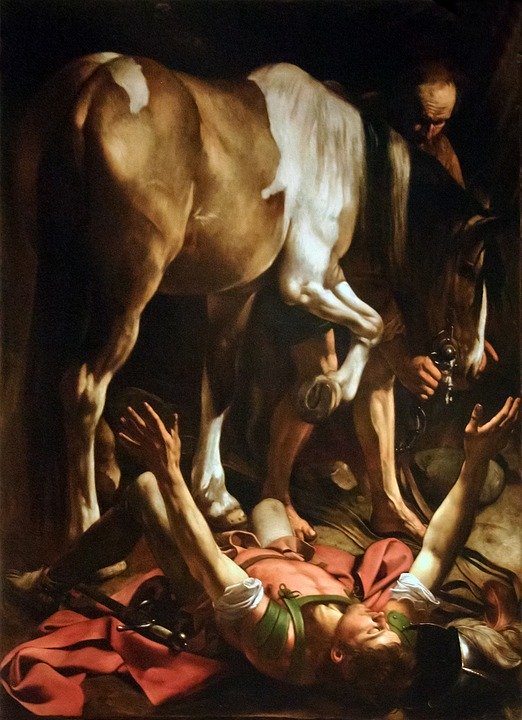

What colour was the horse off which Saul was knocked on the road to Damascus? The Bible doesn’t say. In very fact, the Bible doesn’t mention a horse at all. At some murky point in history, the anonymous quadruped trotted into the popular imagination meditating on the conversion of St. Paul. This is an excellent example of a kind of artistic sensus fidelium, or people’s sense of faith that plugs up visual gaps in belief. Not only does a rearing stallion throwing off an armed and blinded man make for a more dramatic painting, the extra-biblical addition carries theological weight. For the conversion of Paul involved not only his relationship to Christianity, but equally to all of creation.

In a word, his conversion was ecological as well as religious. Hence the horse. Paul was pitched off his seat of domination. He was knocked down from his elevated oppression. He was thrown out of the saddle of crude instrumentalism. Brusquely, involuntarily getting off his high horse, Paul felt the earth for the first time in his faith and life.

Nothing short of radical, unforeseeable conversion could convince a man, once so violently proud to persecute other humans merely for thinking differently, that now he shares a deep kinship with the entire universe. But precisely this new conviction seized hold of the newly baptized Paul. Suddenly, with the scales of an exclusive anthropocentrism falling from his eyes, he sees hopefully “that creation itself would be set free from slavery to corruption and share in the glorious freedom of the children of God. We know that all creation is groaning in labor pains even until now; and not only that, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, we also groan within ourselves as we wait for adoption, the redemption of our bodies” (Romans 8:21-23).

A common destiny shared by humans and the rest of creation. A divine freedom for all creatures promised by God, the loving Creator. Paul wakes up to a relationship with reality that is not primarily utilitarian, self-serving, exclusionary and insensitive. Halfway to Damascus he discovers, as Pope Francis puts it, that the “ultimate purpose of other creatures is not to be found in us. Rather, all creatures are moving forward with us and through us towards a common point of arrival, which is God, in that transcendent fullness where the risen Christ embraces and illumines all things. Human beings, endowed with intelligence and love, and drawn by the fullness of Christ, are called to lead all creatures back to their Creator” (Laudato si, #82).

The faithful imagination rightly could not picture a humbled man, called to lead all creatures back to their Creator, mounted majestically on a bridled horse. He had to be thrown. He had to climb off the bowed back of a poor beast burdened with the oppressive demands of a humanity that considers all other beings as slaves to its needs and whims. That’s why artists have repeatedly, tenaciously introduced the second, hoofed protagonist into the Saul-to-Paul story. With their keen, practiced sight, artists have perceived the cosmic scope of the tireless tentmaker’s conversion. It changed his relationship with the entire material world. Converted, he recognized that he had become, like Christ himself, somehow a servant to creation, in all its human and other-than-human forms. Paul got off his high horse. Paul kicked off the spurs he had used to subjugate creation. Paul started walking and along his interminable travels began to see His face in every flower.

–Greg Kennedy SJ

Greg Kennedy SJ is a Jesuit priest working as a spiritual director at the Ignatius Jesuit Centre in Guelph, Ontario. His prayer often takes the form of poetry. Care of creation is central to his vocation.

On March 1, 2020, his new book, Reupholstered Psalms: Ancient Songs Sung New, will be available for purchase.